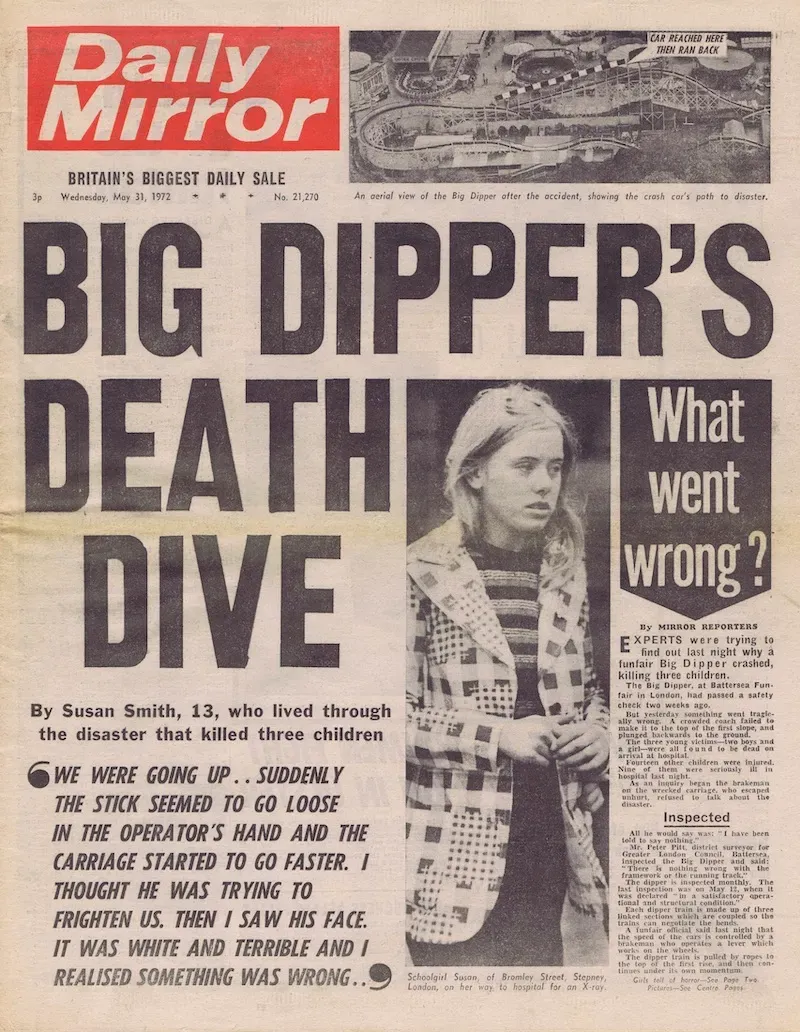

The Battersea Big Dipper Rollercoaster Took A Death Dive And Killed 5 Children

"Screams of joy quickly turned to cries of terror."

They waited in line all day, or at least it felt like all day, but now the long wait was finally over. Some of the smaller children had reached the gate and chickened out at the last second. They walked off, their heads hung in shame as the older children took their spots.

This thrilling new attraction was the John Collins' Big Dipper Rollercoaster—named after the owner. Children praised its large wooden structure and in the summer of 1972, the Big Dipper was a record breaker of both height and speed. Oh, how they would brag in their upcoming classes about how they conquered the epic thrill ride.

And no wonder the smaller kids couldn't hack it—it was just too intimidating. A genuine sight to behold, a wonder of the world—to the children, at least.

Carolyn, now 57, who lives in Eastbourne, said about the Dipper: "It was half-term and I was 14. The funny thing was that my friends and I lived in Hackney and actually wanted to go to the funfair at Walthamstow [in north-east London] but it was closed, so we made a beeline for the big dipper in Battersea, which was the most exciting ride around at the time."

The Big Dipper, a thrill-a-minute joyride which, for 15 pence, is the FASTEST ride in town—so the slogan went.

Noone knew, of course, but the "fastest ride in town" would soon turn into a 65mph death train careening down the 120 foot peak—in reverse.

It was the late afternoon on May 30, 1972, when thirty-one passengers climbed into the Big Dipper's bucket seats, pulling the safety rail down, securing their bodies in place. Out of those, it would kill five children within the first three minutes.

Among the deceased were Shirley Ann Nash (8), Thomas William Harmer (13), David John Sait (14), Deborah Jill Robertson (12), and Alison Sandra Cummerford (15). Thirteen others would be injured, some more severely than others, but would ultimately live. Hilary Wynter—14 at the time—survived, but it took her months of rehabilitation—she had to learn to walk all over again.

The three packed wooden carriages slowly climbed towards the top of the 120 foot summit, being pulled by a steel cable - there was great excitement and anticipation for those on board for the thrills about to come. The rickety wooden structure of the ride creaked and groaned its way along.—Sheila (her survivor story).

In 1972, wooden rollercoasters still used a brakeman to manually slow down at certain points during the ride. Modern coaster technology has succeeded the brakemen with 'up-stop wheels', a nifty technique of adding additional wheels underneath and sides of the track which provide enough 'under friction' to slow down the cars.

As the three-cart coaster "creaked and groaned" up the beginning ramp, the kids shouted with excitement. Everything was functioning normally, just like the last hundred-or-so times.

Rollercoasters like the Big Dipper relied on a large steel haulage wire to pull its heavy load up the big hill. They used the haulage wire only during the initial pull, and once the coaster was at the ride's peak, it would travel the rest of the way using its own kinetic energy.

However, this time, the haulage cable suddenly snapped before the Dipper safely perched itself at the peak.

Now, with nothing supporting the coaster, it rolled backwards, and the lives of the children rested in the hands of the brakeman and the effectiveness of the brakes.

I turned around and was shocked to see the brakeman, who was standing directly behind me and between the first and second carriages, frantically pulling the large steel brake. He had a look of horror as we gathered speed. I realised that we were going to crash if he could not gain control. The screams of joy quickly turned to cries of terror.—Sheila (her survivor story).

The brakes had failed, and the coaster rolled backwards down the 120 foot peak. Nothing would slow it down.

The children screamed.

Every morning, the Big Dipper went through an "inspection", or at least according to its manager, James Hogan. The independent review board who investigated the ride after the crash disagreed with Mr. Hogan's inspection process, as they found sixty-six total defects—eighteen of which were of the support structure.

The inspectors found rotted handrails, "piles" of combustible material—like cardboard and cartons—stashed under the tracks. They found eight of the fire extinguishers "inoperable", so if there was an ignition—keeping in mind the entire ride was made of wood—chances were slim that anyone could snuff the blaze.

"It is not an exaggeration, I think, to say that almost every aspect of the big dipper was found to be defective and some parts gravely defective." Prosecuting attorney Henry Pownall said.

Even the basic task of cleaning the wooden coaster would of at least saved one life. As the coaster raged back down the hill, it threw some passengers from their seating. Alison Cummerford (15) had been thrown from her seat to the wooden walkway stairs about halfway down the coaster's descent. However, when she stepped on the walkway, it was determined that she "slipped on algae" built up on the wooden planks, which caused her body to barrel through the safety handrail. The handrail was supposed to protect her. It did not.

Cummerford fell forty feet to her death.

Carolyn Adamczyk, a passenger interviewed by The Independent, recalled years later "the look of terror on the face of the young girl before she fell to her death. Forty-three years later, she can't erase the image of the pool of blood below the tracks."

When the Dipper reached the sharp curve at the beginning of the ride, it flipped from its tracks. And by then, the death coaster had picked up so much velocity that it derailed. The twisting and thrashing caused it to basically rip itself to pieces, dumping the screaming children wherever it could.

The seats had splintered on impact, causing even more damage to the mangled bodies. As the adults rushed in to pick up the pieces, they saw firsthand the devastation and destruction.

In the initial moments following the crash, there was silence, then people started screaming and crying. All the expected fun of the fair had ended in tragedy.—Sheila (her survivor story).

The tragic event eventually caused the entire park to be torn down in 1974. The Big Dipper burned down because of an arson attack, so it was probably for the better. It's also interesting to know that a few people that I have asked—who live close to the Battersea Park area—did not know that a theme park ever existed there at all.

This event was surely horrible. Five children were dead within minutes and it's no doubt that Sheila and all the other survivors who rode the Big Dipper that day still have the occasional panic attack.

For me, I'll stick to the spinning tea cups.