The Pockmarked Killer 'Le Grêlé': How a French Cop Terrorized Paris for Decades

For over 35 years, a sadistic serial killer and rapist known as "Le Grêlé" ("The Pockmarked Man") stalked the streets of Paris, preying on young girls and leaving a trail of unsolved crimes that haunted the city.

Listen to this article

Recorded with Shure microphone.

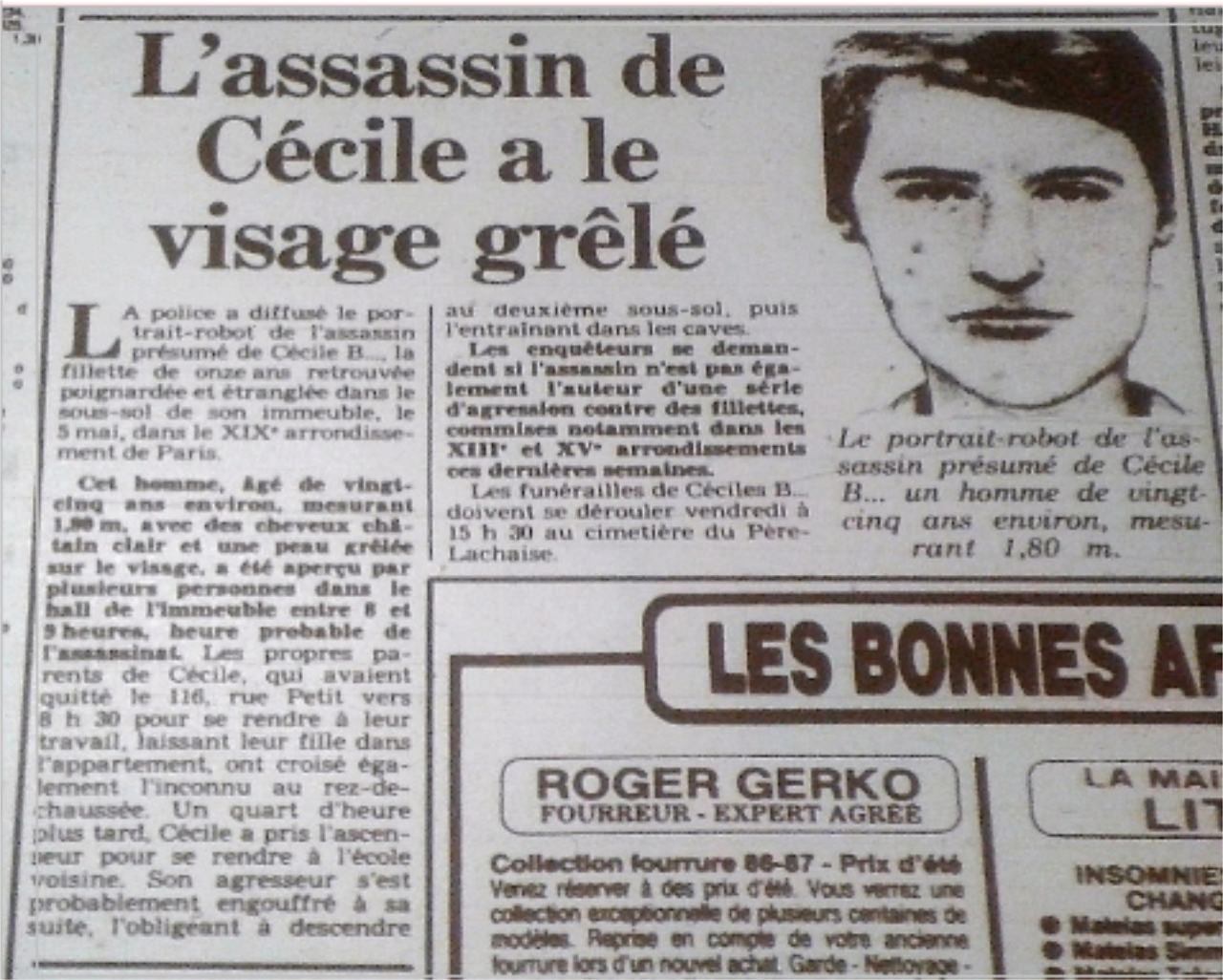

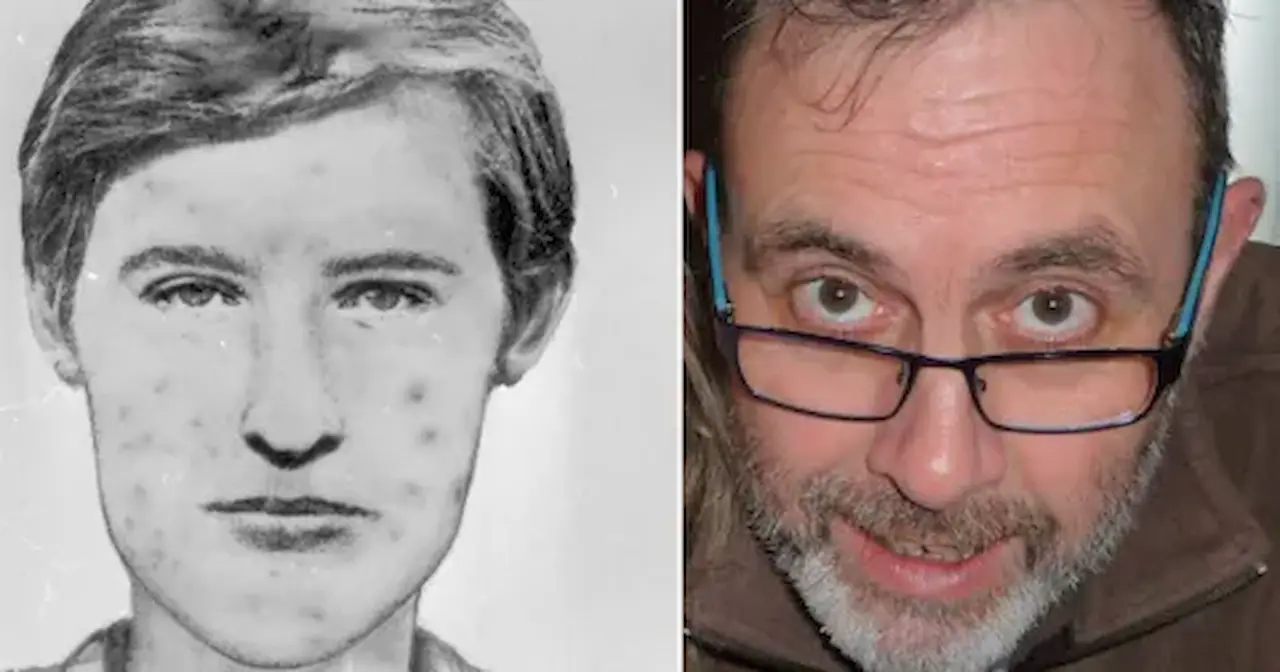

Witnesses described a man with a distinctively scarred and acne-pitted face—yet despite having his DNA, fingerprints, and a clear suspect sketch, police failed to catch Le Grêlé for decades.

The reason for their failure became shockingly clear in September 2021, when 59-year-old François Vérove, a former French police officer, took his own life and left behind a confession identifying himself as the notorious Le Grêlé. Vérove had managed to evade capture by his fellow officers during his years on the force. His suicide brought an end to one of France's most enduring criminal mysteries, but denied his victims and their families long-awaited justice.

A Reign of Terror Begins

Le Grêlé's first known attack occurred on January 13, 1984, when he assaulted 11-year-old Do Pham in the elevator of her Paris apartment building. Pham recognized him as the same man who had been in the elevator asking about a "Martin" the day before. This time, he grabbed the girl, hit her head against the wall, and led her to a basement room with a mattress inside. He ordered her to undress at knifepoint and lie face-down before rubbing against her and fleeing.

Pham gave police a detailed description of her attacker: a European man, quite thin, with a triangular face, pale complexion, light brown hair, and poorly shaven. He spoke French without an accent. This matched the account of 8-year-old Sarah A., who was raped a few months later in April 1986 by a man who dragged her to a basement. The girl barely survived being strangled with a cord.

On May 5, 1986, Le Grêlé committed his most notorious crime—the rape and murder of 11-year-old Cécile Bloch. That morning, several witnesses, including Cécile's half-brother Luc Richard, recalled seeing a man with a pockmarked face in the elevator of their building at 116 Rue Petit. "He said something to me like, 'Have a very, very good day,'" Luc later recalled.

When Cécile failed to arrive at school, her mother discovered her body in the basement, half-naked under a piece of carpet. She had been raped, stabbed, and strangled so violently her spine was broken. Police recovered the killer's semen from the scene. Three days later, another young girl named Nathalie M. was assaulted, and she recognized Cécile's killer from a police sketch.

Escalating Violence

Nearly a year after Cécile Bloch's murder, on April 29, 1987, Le Grêlé carried out his most brutal attack yet. He entered the apartment of Gilles Politi, 38, and Irmgard Müller, 20, the German au pair for Politi's young daughter. In a scene one officer called "the most incredible crime scene of his career," the couple was found dead the next day in a "hog-tied" position—bound, stripped, with their throats slit and cigarette burns on their bodies. Müller had been raped and suspended from a bed frame.

Police recovered DNA evidence from a cigarette butt and semen at the scene. They believed the killer likely knew Müller, as her address book contained a false name, "Élie Lauringe," which was probably the killer's pseudonym.

A Suspect Hiding in Plain Sight

As the years went by, more young female victims between the ages of 11-14 came forward to report rapes and attempted abductions by a pockmarked man across the Paris region. Police developed a clear suspect sketch. In 1996, they recovered the attacker's DNA from several crime scenes, including Cécile Bloch's murder, allowing them to link the crimes to a single perpetrator.

However, no DNA matches were found in France's criminal database. Unbeknownst to authorities, their suspect was in fact one of their own—François Vérove, who had been a gendarme since the 1980s. He joined the Paris police force in 1988, a year after the Politi-Müller double murder, and served until his retirement in 2019.

Vérove's police status likely allowed him to stay a step ahead of investigators and avoid having his DNA collected. "We know that he was in the police force and that he was involved in police investigations," said Laurent Nahon, lawyer for Cécile Bloch's family. "He was able to get information and hide things. He was really playing with us."

A Deathbed Confession

Vérove's luck finally ran out in September 2021, when magistrates investigating the old Le Grêlé cases ordered him to provide a DNA sample. Days later, the 59-year-old was reported missing by his wife on September 27. On September 29, his body was found in a rented apartment in the southern town of Le Grau-du-Roi, nearly 500 miles from Paris.

Vérove died by suicide, leaving behind multiple confession notes. "My name is François Vérove," he wrote on his ID card. "I have just committed suicide. In case I'm in a coma DO NOT TRY TO RESUSCITATE ME, THANK YOU". On the kitchen hood, he scrawled: "SUICIDE PLEASE CALL 17 (french 911)".

In a letter to his family, Vérove explained his crimes: "Sometimes I couldn't take it anymore, and I had to destroy, tarnish, kill innocent people," he wrote. "Therapy erased my death instinct: when I was killing innocent people, I was actually seeking to destroy my childhood wounds".

DNA taken from Vérove's body conclusively matched evidence from the Le Grêlé crime scenes. Paris prosecutor Laure Beccuau confirmed "DNA tests which were immediately ordered by the investigating magistrate established a match between the genetic profile found at several crime scenes and that of the dead man".

An Overdue End

Vérove's identification as Le Grêlé brought some closure to a case that had stymied French police for nearly four decades. Didier Saban, lawyer for the family of murder victim Irmgard Müller, expressed relief: "The victims' families will be able to sleep soundly tonight, knowing that the killer is no longer at large".

However, Vérove's suicide robbed his victims of true justice and left lingering questions about how a predator could operate within the police's own ranks for so long. Cécile Bloch's half-brother Luc Richard lamented the lost opportunity to confront the killer: "I would have liked to look him in the eye, to ask him why he did it. It won't be possible. It's a great disappointment".

While the case of Le Grêlé has finally been solved, it serves as a chilling reminder that sometimes the most dangerous criminals are hiding in plain sight, cloaked in the very authority meant to stop them. For the families whose lives he destroyed, Vérove's confession is a long-overdue reckoning, but one that came decades too late.